May 6, 2021

System Design Interview

Besides reading this post, I strongly recommend reading chapter 4 (Design a Rate Limiter) of the book System Design Interview – An insider’s guide (Xu, Alex) You can review alternative resources as well.

- Let’s imaging we launched a web application. And the application became highly popular. Meaning that thousands of clients send thousands of requests every second to the front-end web service of our application. Everything works well. Until suddenly one or several clients started to send much more requests than they did previously. And this may happen due to a various of reasons.

- For example, our client is another popular web service and it experienced a sudden traffic spike.

- Or developers of that web service started to run a load test.

- Or this is just a malicious client who tried to DDoS our service.

- All these situations may lead to a so called “noisy neighbor problem”, when one client utilizes too much shared resources on a service host, like CPU, memory, disk or network I/O.

- And because of this, other clients of our application start to experience higher latency for their requests, or higher rate of failed requests.

- One of the ways to solve a “noisy neighbor problem” is to introduce a rate limiting (also known as throttling).

- Throttling helps to limit the number of requests a client can submit in a given amount of time.

- Requests submitted over the limit are either immediately rejected or their processing is delayed.

- Some questions:

- This problem does not have a lot of sense. It should be solved by scaling out the cluster of hosts that run our web service. And ideally, by some kind of auto-scaling. -> And the problem with scaling up or scaling out is that it is not happening immediately. Even autoscaling takes time. And by the time scaling process completes it may already be late. Our service may already crash.

- How rate limiting can be achieved? Specifically, you mention load balancers and their ability to limit a number of simultaneous requests that load balancer sends to each application server. -> Load balancers indeed may prevent too many requests to be forwarded to an application server. Load balancer will either reject any request over the limit or send the request to a queue, so that it can be processed later. But the problem with this mechanism – it is indiscriminate. Let’s say our web service exposes several different operations. Some of them are fast operations, they take little time to complete. But some operations are slow and heavy and each request may take a lot of processing power. Load balancer does not have knowledge about a cost of each operation. And if we want to limit number of requests for a particular operation, we can do this on application server only, not at a load balancer level.

- The problem does not seem to be a system design problem. Algorithmic problem? -> Yes, as we need to define data structures and algorithm to count how many requests client has made so far.

- Object-oriented design problem? -> Probably, as we may need to design a set of classes to manage throttling rules. Rules define an allowed throttling limit for each operation.

- So, if we implement throttling for a single host, are we done? -> In an ideal world – yes. But not in the real world. If we have a load balancer in front of our web service and this load balancer spreads requests evenly across application servers and each request takes the same amount of time to complete. In this case this is a single instance problem and there is no need in any distributed solution. Application servers do not need to talk to each other. They throttle requests independently. But in the real-world load balancers cannot distribute requests in a perfectly even manner. Plus, as we discussed before different web service operations cost differently. And each application server itself may become slow due to software failures or overheated due to some other background process running on it. All this leads to a conclusion that we will need a solution where application servers will communicate with each other and share information about how many client requests each one of them processed so far.

Functional Requirements

- allowRequest(request) : For a given request our rate limiting solution should return a boolean value, whether request is throttled or not.

Non-Functional Requirements

- Low Latency (We need rate limiter to be fast (as it will be called on every request to the service)

- Accurate (We do not want to throttle customers unless it is absolutely required)

- Scalable (Rate limiter scales out together with the service itself, if we need to add more hosts to the web service cluster, this should not be a problem for the rate limiter)

- What about high availability and fault tolerance? Two common requirements for many distributed systems. Are they important for a rate limiting solution? -> Not so much. If rate limiter cannot make a decision quickly due to any failures, the decision is always not to throttle. If we do not know whether throttle or not -> we do not throttle. Because we may need to introduce rate limiting in many services, the interviewer may ask us to think about ease of integration. So that every service team in the organization can integrate with our rate limiting solution as seamlessly as possible. This is a good requirement.

- Let’s implement a rate limiting solution for a single server first. So, no communication between servers just yet.

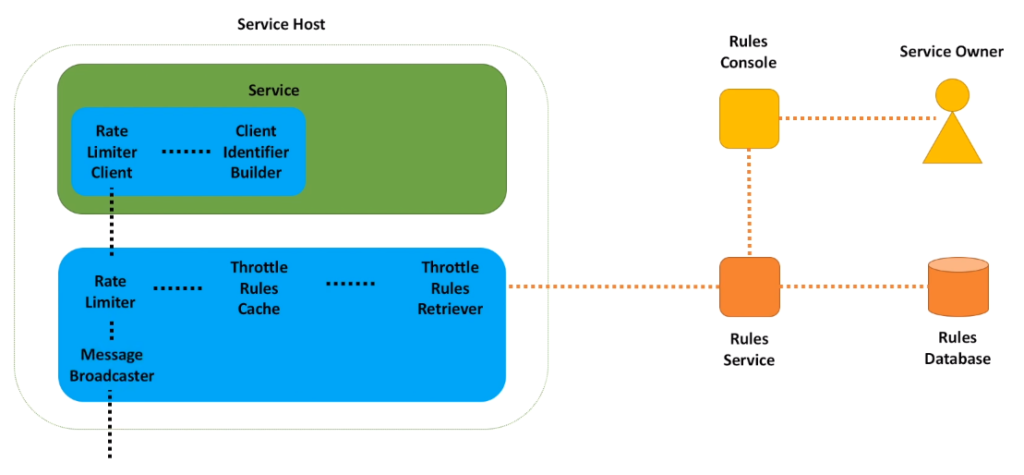

- The first citizen of the rate limiting solution on the service host is the rules retriever.

- Each rule specifies a number of requests allowed for a particular client per second.

- These rules are defined by service owners and stored in a database.

- And there is a web service that manages all the operation with rules.

- Rules retriever is a background process that polls Rules service periodically to check if there are any new or modified rules.

- Rules retriever stores rules in memory on the host.

- When request comes, the first thing we need to do is to build a client identifier.

- Let’s call it a key, for short.

- This may be a login for registered clients or remote IP address or some combination of attributes that uniquely identify the client.

- The key is then passed to the Rate Limiter component, that is responsible for making a decision.

- Rate Limiter checks the key against rules in the cache.

- And if match is found, Rate Limiter checks if number of requests made by the client for the last second is below a limit specified in the rule.

- If threshold is not exceeded, request is passed further for processing.

- If threshold is exceeded, the request is rejected.

- And there are three possible options in this case.

- Our service may return a specific response status code, for example service unavailable or too many requests.

- Or we can queue this request and process it later.

- Or we can simply drop this request on the floor.

- We know we need a database to store the rules.

- And we need a service on top of this database for all the so-called CRUD operations (create, read, update, delete).

- We know we need a process to retrieve rules periodically.

- And store rules in memory.

- And we need a component that makes a decision.

- You may argue whether we need the client identifier builder as a separate component or should it just be a part of the decision-making component.

- It is up to you.

- I wanted to present this builder as a separate component to stress the point that client identification is an important step of the whole process.

- From here interview may go in several directions. Interviewer may be interested in the Rate Limiter algorithm and ask us to implement one.

- Or interviewer may be interested in object-oriented design and ask us to define main classes and interfaces of the throttling library.

- Or interviewer may ask us to focus on a distributed throttling solution and discuss how service hosts share data between each other.

- Let’s discuss each of these possible directions.

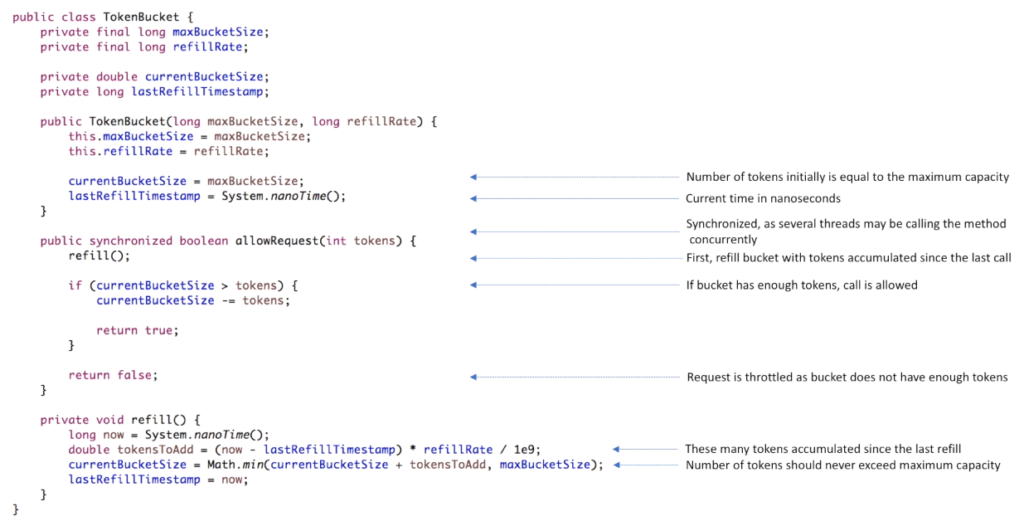

Token Bucket Algorithm

- There are many different algorithms to solve this problem. You may find inspiration by looking into Google Guava RateLimiter class. Or think about how fixed and sliding window paradigms can be applied. But probably the simplest algorithm out there is the Token Bucket algorithm.

- The token bucket algorithm is based on an analogy of a bucket filled with tokens.

- Each bucket has three characteristics: a maximum amount of tokens it can hold, amount of tokens currently available and a refill rate, the rate at which tokens are added to the bucket.

- Every time request comes, we take a token from the bucket.

- If there are no more tokens available in the bucket, request is rejected.

- And the bucket is refilled with a constant rate.

- The beauty of the Token Bucket algorithm is that it simple to understand and simple to implement.

- There are 4 class fields: maximum bucket size, refill rate, number of currently available tokens and timestamp that indicates when bucket was last refilled.

- Constructor accepts two arguments: maximum bucket size and refill rate.

- Number of currently available tokens is set to the maximum bucket size.

- And timestamp is set to the current time in nanoseconds.

- Allow request method has one argument – number of tokens that represent a cost of the operation.

- Usually, the cost is equal to 1.

- Meaning that with every request we take a single token from the bucket.

- But it may be a larger value as well.

- For example, when we have a slow operation in the web service and each request to that operation may cost several tokens.

- The first thing we do is refilling the bucket.

- And right after that we check if there are enough tokens in the bucket.

- In case there are not enough tokens, method return false, indicating that request must be throttled.

- Otherwise, we need to decrease number of available tokens by the cost of the request.

- And the last piece is the refill method.

- It calculates how many tokens accumulated since the last refill and increases currently available tokens in the bucket by this number.

Interfaces & Classes

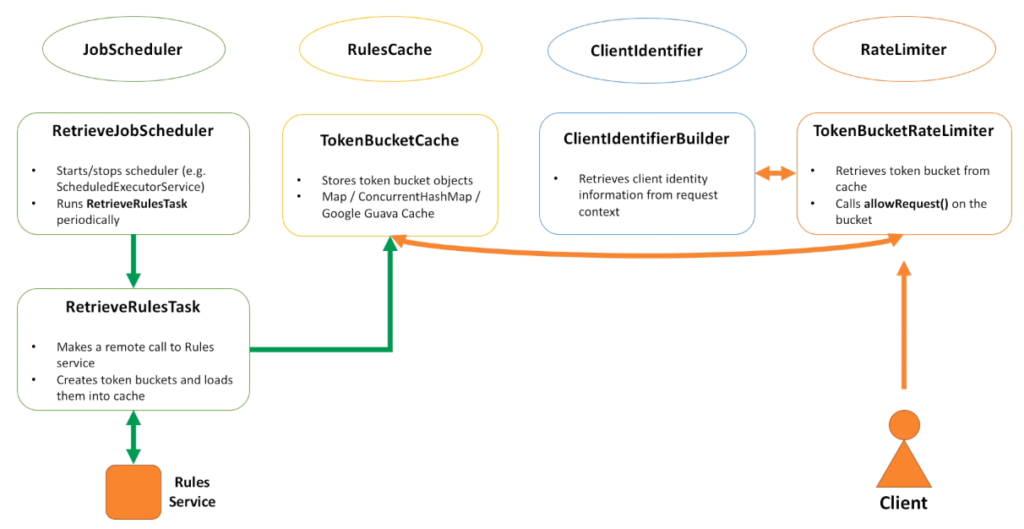

- Job Scheduler interface is responsible for scheduling a job that runs every several seconds and retrieves rules from Rules service.

- RulesCache interface is responsible for storing rules in memory.

- ClientIdentifier builds a key that uniquely identifies a client.

- And RateLimiter is responsible for decision making.

- RetrieveJobScheduler class implements JobScheduler interface.

- Its responsibility is to instantiate, start and stop the scheduler.

- And to run retrieve rules task.

- TokenBucketCache stores token buckets.

- We can use something simple, for example Map to store buckets.

- Or utilize 3-rd party cache implementation, like Google Guava cache.

- ClientIdentifierBuilder is responsible for building a key based on user identity information (for example login).

- There can be other implementations as well, for example based on IP address.

- And for the RateLimiter interface lets introduce a TokenBucketRateLimiter class, which is responsible for calling allow request on the correspondent bucket for that client.

- And the last important piece is the RetrieveRulesTask, which is responsible for retrieving all the rules for this service.

- Let’s look at how these components interact with each other.

- Hopefully, it will help you to better remember all the components.

- RetrieveJobScheduler runs RetrieveRulesTask, which makes a remote call to the Rules service.

- It then creates token buckets and puts them into the cache.

- When client request comes to the host, RateLimiter first makes a call to the ClientIdentifierBuilder to build a unique identifier for the client.

- And then it passes this key to the cache and retrieves the bucket.

- And the last step to do is to call allow request on the bucket.

Step into the distributed world

- We have a cluster that consists of 3 hosts. And we want rate limiting solution to allow 4 requests per second for each client. How many tokens should we give to a bucket on every host?

- Should we give 4 divided by 3? And the answer is 4.

- Each bucket should have 4 tokens initially.

- The reason for this is that all requests for the same bucket may in theory land on the same host.

- Load balancers try to distributed requests evenly, but they do not know anything about keys, and requests for the same key will not be evenly distributed.

- Let’s add load balancer into the picture and run a very simple simulation.

- The first request goes to host A, one token is consumed.

- The second request goes to host C and one token is consumed there.

- Two other requests, within the same 1 second interval, go to host B. And take two tokens from the bucket.

- All 4 allowed requests hit the cluster; we should throttle all the remaining requests for this second.

- But we still have tokens available. What should we do?

- We must allow hosts to talk to each other and share how many tokens they consumed altogether.

- In this case host A will see that other two hosts consumed 3 tokens. And host A will subtract this number from its bucket. Leaving it with 0 tokens available.

- Host B will find out that A and C consumed two tokens already. Leaving host B with 0 tokens as well.

- And the same logic applies to host C. Now everything looks correct.

- 4 requests have been processed and no more requests allowed.

- We gave each bucket 4 tokens. If many requests for the same bucket hit our cluster exactly at the same second. Does this mean that 12 requests may be processed, instead of only 4 allowed?

- Or may be a more realistic scenario.

- Because communication between hosts takes time, until all hosts agree on what that final number of tokens must be, may there be any requests that slip into the system at that time?

- Yes. Unfortunately, this is the case.

- We should expect that sometimes our system may be processing more requests than we expect and we need to scale out our cluster accordingly.

- By the way, the token bucket algorithm will still handle this use case well.

- We just need to slightly modify it to allow negative number of available tokens.

- When 12 requests hit the system, buckets will start sharing this information.

- After sharing, every bucket will have -8 tokens and for the duration of the next 2 seconds all requests will be throttled.

- So, on average we processed 12 requests within 3 seconds.

- Although in reality all 12 were processed within the first second.

- So, communication between hosts is the key.

- Let’s see how this communication can be implemented.

- By the way, ideas we will discuss next are applicable not only for rate limiting solution, but many other distributed systems that require data sharing between all hosts in a cluster in a real time.

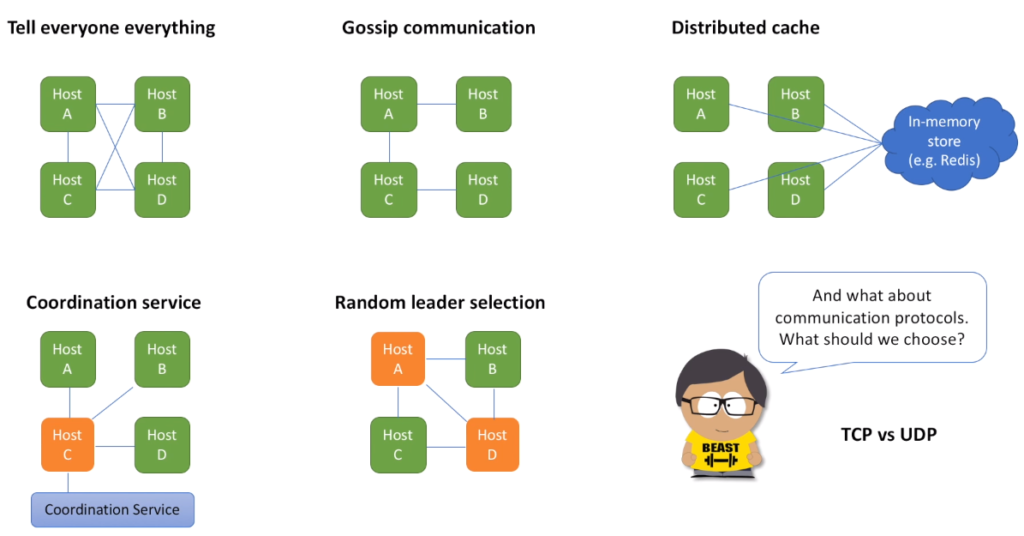

Message Broadcasting

- The first approach is to tell everyone everything. It means that every host in the cluster knows about every other host in the cluster and share messages with each one of them. You may also heard a term full mesh that describes this network topology. How do hosts discover each other? When a new host is added, how does everyone else know? And there are several approaches used for hosts discovery. One option is to use a 3-rd party service which will listen to heartbeats coming from every host. As long as heartbeats come, host is keep registered in the system. If heartbeats stop coming, the service unregister host that is no longer alive. And all hosts in our cluster ask this 3-rd party service for the full list of members. Another option is to resolve some user provided information. For example, user specifies a VIP and because VIP knows about all the hosts behind it, we can use this information to obtain all the members. Or we can rely on a less flexible but still a good option when user provides a list of hosts via some configuration file. We then need a way to deploy this file across all cluster nodes every time this list changes. Full mesh broadcasting is relatively straightforward to implement. But the main problem with this approach is that it is not scalable. Number of messages grows quadratically with respect to the number of hosts in a cluster. Approach works well for small clusters, but we will not be able to support big clusters.

- So, let’s investigate some other options that may require less messages to be broadcasted within the cluster. And one such option is to use a gossip protocol. This protocol is based on the way that epidemics spread. Computer systems typically implement this type of protocol with a form of random “peer selection”: with a given frequency, each machine picks another machine at random and shares data. By the way, rate limiting solution at Yahoo uses this approach.

- Next option is to use distributed cache cluster. For example, Redis. Or we can implement custom distributed cache solution. The pros for this approach is that distributed cache cluster is relatively small and our service cluster can scale out independently. This cluster can be shared among many different service teams in the organization. Or each team can setup their own small cluster.

- Next approach also relies on a 3-rd party component. A coordination service that helps to choose a leader. Choosing a leader helps to decrease number of messages broadcasted within the cluster. Leader asks everyone to send it all the information. And then it calculates and sends back the final result. So, each host only needs to talk to a leader or a set of leaders, where each leader is responsible for its own range of keys. Consensus algorithms such as Paxos and Raft can be used to implement Coordination Service. Great option, but the main drawback is that we need to setup and maintain Coordination Service. Coordination service is typically a very sophisticated component that has to be very reliable and make sure one and only one leader is elected. But is this really a requirement for our system?

- Let’s say we use a simple algorithm to elect a leader. But because of the simplicity of the algorithm it may not guarantee one and only one leader. So that we may end up with multiple leaders being elected. Is this an issue? Actually, no. Each leader will calculate rate and share with everyone else. This will cause unnecessary messaging overhead, but each leader will have its own correct view of the overall rate.

- And to finish message broadcasting discussion, I want to talk about communication protocols, how hosts talk to each other. We have two options here: TCP and UDP.

- TCP protocol guarantees delivery of data and also guarantees that packets will be delivered in the same order in which they were sent.

- UDP protocol does not guarantee you are getting all the packets and order is not guaranteed. But because UDP throws all the error-checking stuff out, it is faster.

- So, which one is better? Both are good choices.

- If we want rate limiting solution to be more accurate, but with a little bit of performance overhead, we need to go with TCP.

- If we ok to have a bit less accurate solution, but the one that works faster, UDP should be our choice.

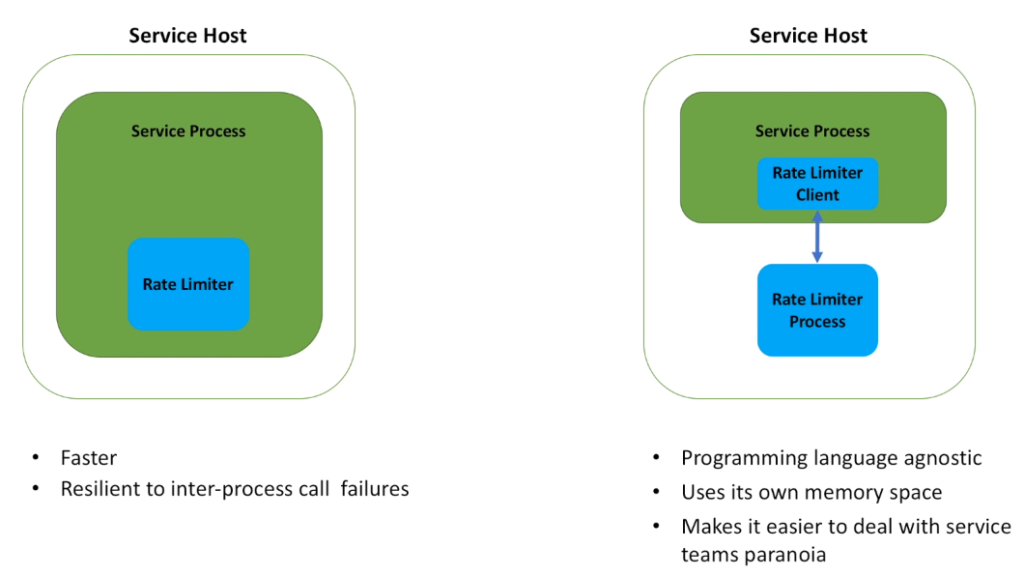

How do we integrate all

- There are two options. And they are pretty standard. We can run Rate Limiter as a part of the service process or as its own process (daemon).

- In the first option, Rate Limiter is distributed as a collection of classes, a library that should be integrated with the service code.

- In the second option we have two libraries: the daemon itself and the client, that is responsible for inter-process communication between the service process and the daemon. Client is integrated with the service code.

- What are the pros for the first approach?

- It is faster, as we do not need to do any inter-process call.

- It is also resilient to the inter-process call failures, because there are no such calls. -The second approach is programming language agnostic. It means that Rate Limiter daemon can be written on a programming language that may be different from the language we use for the service implementation. As we do not need to do integration on the code level. Yes, we need to have Rate Limiter client compatible with the service code language. But not the daemon itself.

- Also, Rate Limiter process uses its own memory space. This isolation helps to better control behavior for both the service and the daemon. For example, daemon my store many buckets in memory, but because the service process has its own memory space, the service memory does not need to allocate space for these buckets. Which makes service memory allocation more predictable.

- Another good reason, and you may see it happening a lot in practice, service teams tend to be very cautious when you come to them and ask to integrate their service with your super cool library.

- You will hear tons of questions.

- Like how much memory and CPU your library consumes?

- What will happen in case of a network partition or any other exceptional scenario?

- Can we see results of the load testing for your library?

- These questions are also applicable to the daemon solution.

- But it is easier to guarantee that the service itself will not be impacted by any bugs that may be in the Rate Limiter library.

- As you may see, strengths of the first approach become weaknesses of the second approach. And vice versa.

- So, which option is better?

- Both are good options and it really depends on the use cases and needs of a particular service team.

- By the way, the second approach, when we have a daemon that communicates with other hosts in the cluster is a quite popular pattern in distributed systems.

- For example, it is widely used to implement auto discovery of service hosts, when hosts in a cluster identify each other.

What else?

- In theory, it is possible that many token buckets will be created and stored in memory. For example, when millions of clients send requests at the same second. In practice though, we do not need to keep buckets in memory if there are no requests coming from the client for some period of time. For example, client made its first request and we created a bucket. As long as this client continues to send requests and interval between these requests is less than a second or couple of seconds, we keep the bucket in memory. If there are no requests coming for this bucket for several seconds, we can remove the bucket from memory. And bucket will be re-created again when client makes a new request.

- As for failure modes, there may be several of them. Daemon can fail, causing other hosts in the cluster lose visibility of this failed daemon. In the result, the host with a failed daemon leaves the group and continues to throttle requests without talking to other hosts in the cluster. Nothing really bad happens. Just less requests will be throttled in total. And we will have similar results in case of a network partition, when several hosts in the cluster may not be able to broadcast messages to the rest of the group. Just less requests throttled in total. And if you wonder why, just remember our previous example with 3 hosts and 4 tokens. If hosts talk to each other, only 4 requests are allowed across all of them. If hosts do not talk to each other due to let’s say network issues, each host will allow 4 requests, 12 in total. So, in case of failures in our rate limiter solution, more requests are allowed and less requests are throttled.

- With regards to rule management, we may need to introduce a self-service tool, so that service teams may create, update and delete their rules when needed.

- As for synchronization, there may be several places where we need it. First, we have synchronization in the token bucket. There is a better way to implement thread-safety in that class, using for example atomic references. Another place that may require synchronization is the token bucket cache. As we mentioned before, if there are too many buckets stored in the cache and we want to delete unused buckets and re-create them when needed, we will end up with synchronization. So, we may need to use concurrent hash map, which is a thread safe equivalent of the hash map in Java. In general, no need to be afraid of the synchronization in both those places. It may become a bottleneck eventually, but only for services with insanely large requests per second rate. For most services out there even the simplest synchronization implementation does not add to much overhead.

- So, what clients of our service should do with throttled calls? There are several options, as always. Clients may queue such requests and re-send them later. Or they can retry throttled requests. But do it in a smart way, and this smart way is called exponential backoff and jitter. Probably too smart. But do not worry, ideas are quite simple. An exponential backoff algorithm retries requests exponentially, increasing the waiting time between retries up to a maximum backoff time. In other words, we retry requests several times, but wait a bit longer with every retry attempt. And jitter adds randomness to retry intervals to spread out the load. If we do not add jitter, backoff algorithm will retry requests at the same time. And jitter helps to separate retries.

Final look

- Service owners can use a self-service tools for rules management.

- Rules are stored in the database.

- On the service host we have rules retriever that stores retrieved rules in the local cache.

- When request comes, rate limiter client builds client identifier and passes it to the rate limiter to make a decision.

- Rate limiter communicates with a message broadcaster, that talks to other hosts in the cluster.

- We wanted to build a solution that is highly scalable, fast and accurate.

- And at this point I would really like to say that the solution we have built meets all the requirements. But this is not completely true. And the correct answer is “it depends”.

- Depends on the number of hosts in the cluster, depends on the number of rules, depends on the request rate.

- For majority of clusters out there, where cluster size is less then several thousands of nodes and number of active buckets per second is less then tens of thousands, gossip communication over UDP will work really fast and is quite accurate.

- In case of a rally large clusters, like tens of thousands of hosts, we may no longer rely on host-to-host communication in the service cluster as it becomes costly.

- And we need a separate cluster for making a throttling decision.

- This is a distributed cache option we discussed above.

- But the drawback of this approach is that it increases latency and operational cost.

- It would be good to have these tradeoff discussions with your interviewer.

- As it demonstrates both breadth and depth of your knowledge and critical thinking.

This content was excerpted from here.